Boundaries, 2017.

Boundaries (Two Ponds Press, 2017) is one of our newest acquisitions and a favorite fine press book among Special Collections staff. (N.B.: as of the post date, Special Collections is the only holding library for this title in Texas – Jason) With poems by Richard Blanco and photographs by Jacob Bond Hessler, the volume addresses social divisions that have burdened our country’s history and exposes the ways these boundaries continue to trouble us.

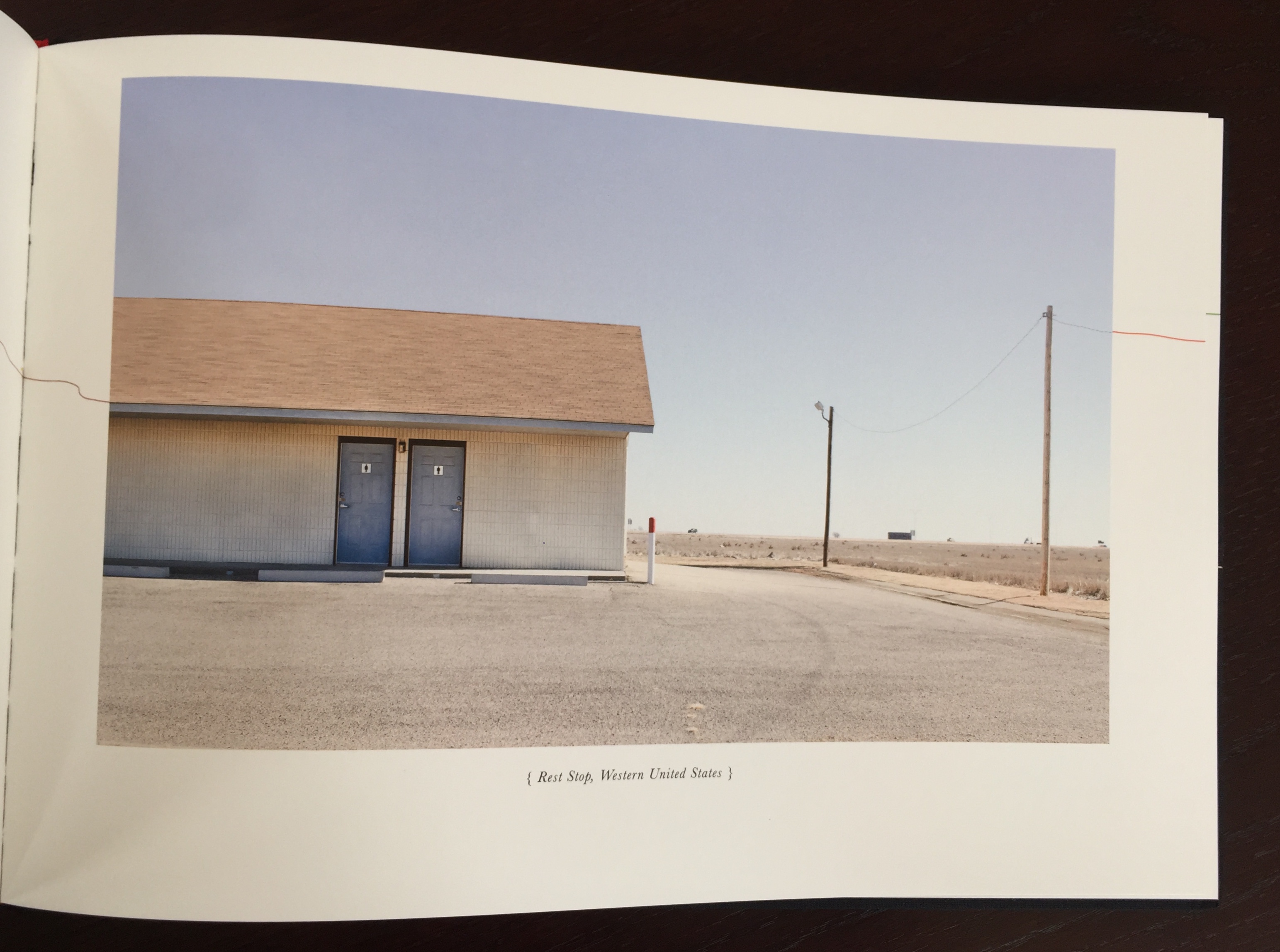

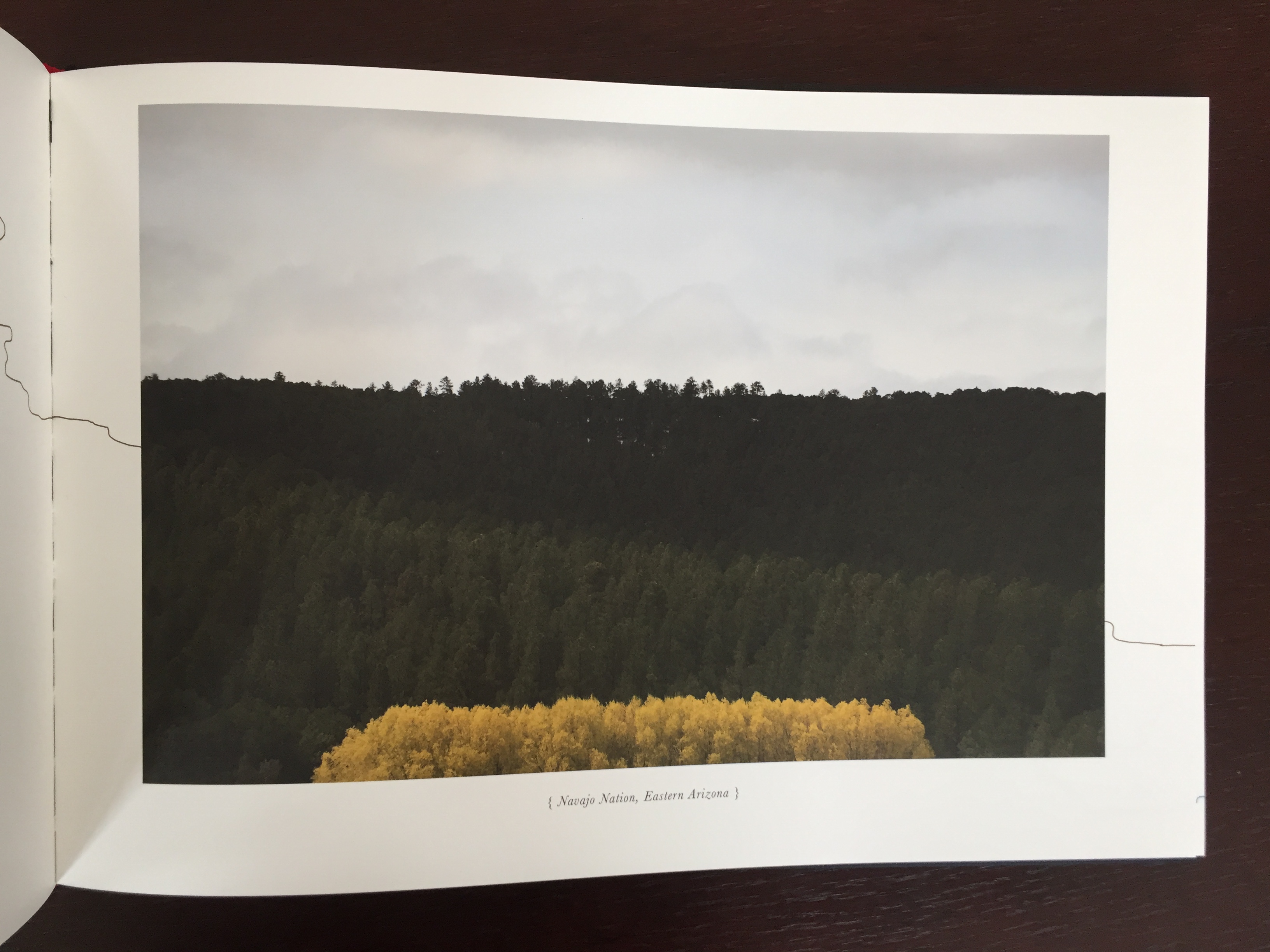

Boundaries puts the geographic and social awareness of its contributors on display. The photographs capture numerous regions of the United States, from Maine to Texas, San Francisco to Mobile, the land of the Navajo Nation in Arizona to Hallandale Beach in Florida. Each image is laden with historical significance which Blanco interprets in an accompanying poem. Together, the photograph and the words reveal societal divisions on topics such as race and gender.

To this end, Hessler’s design of the book is thoughtfully simple. Lines of changing color meander across the pages of Boundaries, resembling borders on maps. The lines weave around poems and behind photographs, jagged in some places, and smooth in others. These borders match up with lines discernible in the photographs. The book’s design thus interacts with Hessler’s images to underscore the visible and invisible boundaries that fragment our nation.

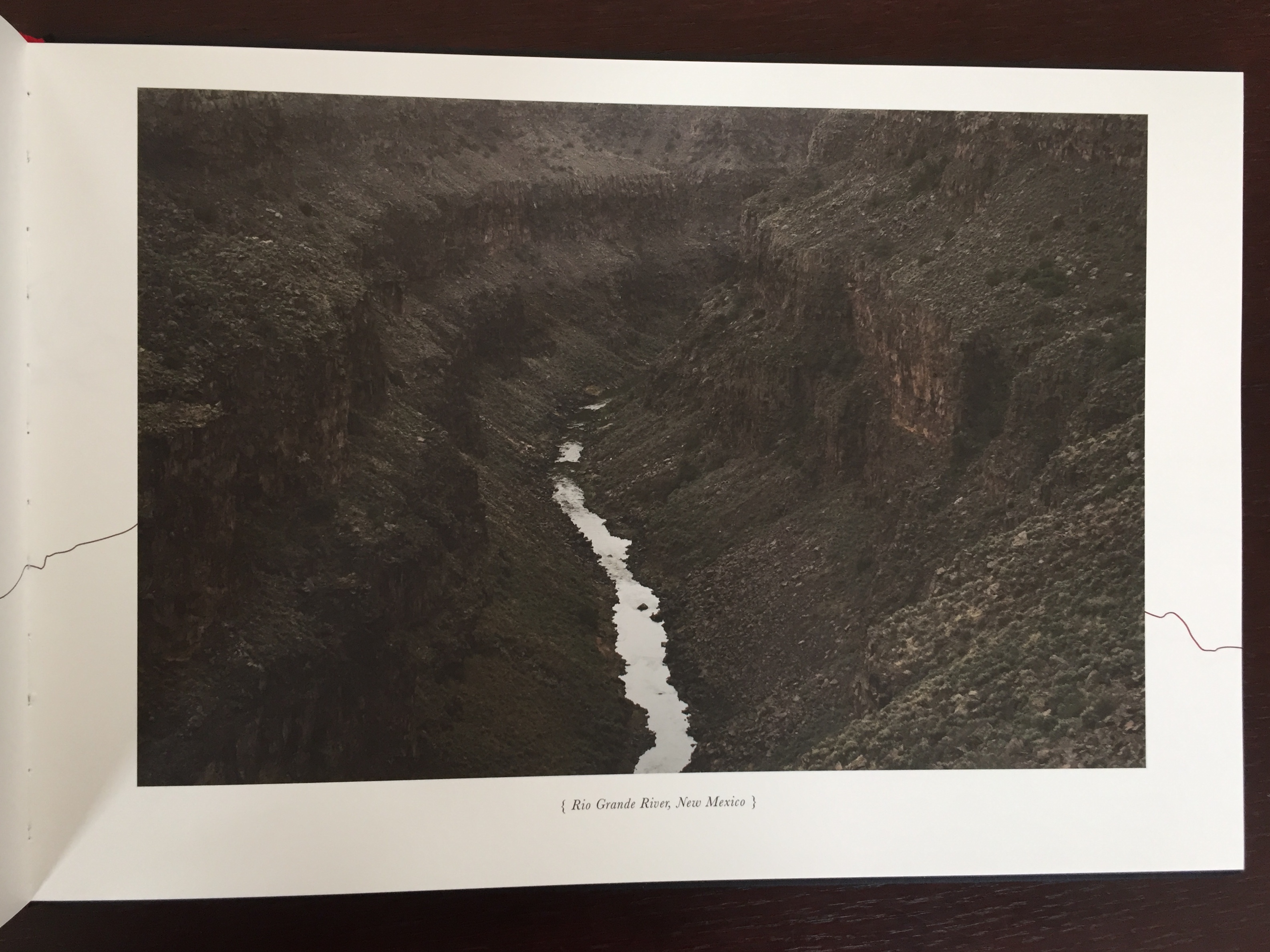

With their content, Blanco and Hessler infuse literal, physical boundaries with personal and historical weight. In his poem “Complaint of the Rio Grande” Blanco personifies the river that forms the border between the United States and Mexico. The poem reads in part, “I wasn’t meant to drown children, hear / mothers’ cries, never meant to be your / geography: a line, a border, or murderer. / I was meant for all things to meet.” Across the page is Hessler’s photograph of the Rio Grande in New Mexico, surrounded by impressively steep canyon walls that speak to the generations of its steady flow:

Similarly, Blanco’s poem “Staring at Aspens: a History Lesson” mourns the abuse of the Navajo people by the United States government during their compulsory relocation in 1864. The corresponding image shows a dense forest of aspen trees, looking both majestic and somber, a boundary crossed by many of the Navajo people during the forced migration from their land:

Some of the boundaries that Blanco and Hessler explore in the volume are less literal. Blanco writes about boundaries of gender in “Between [Another Door]” and about political divides in “Election Year” and “November Eyes on Main Street.” Although each poem is set in a highly specific location, the images and text are so flawlessly intertwined that they seem personal to the reader.

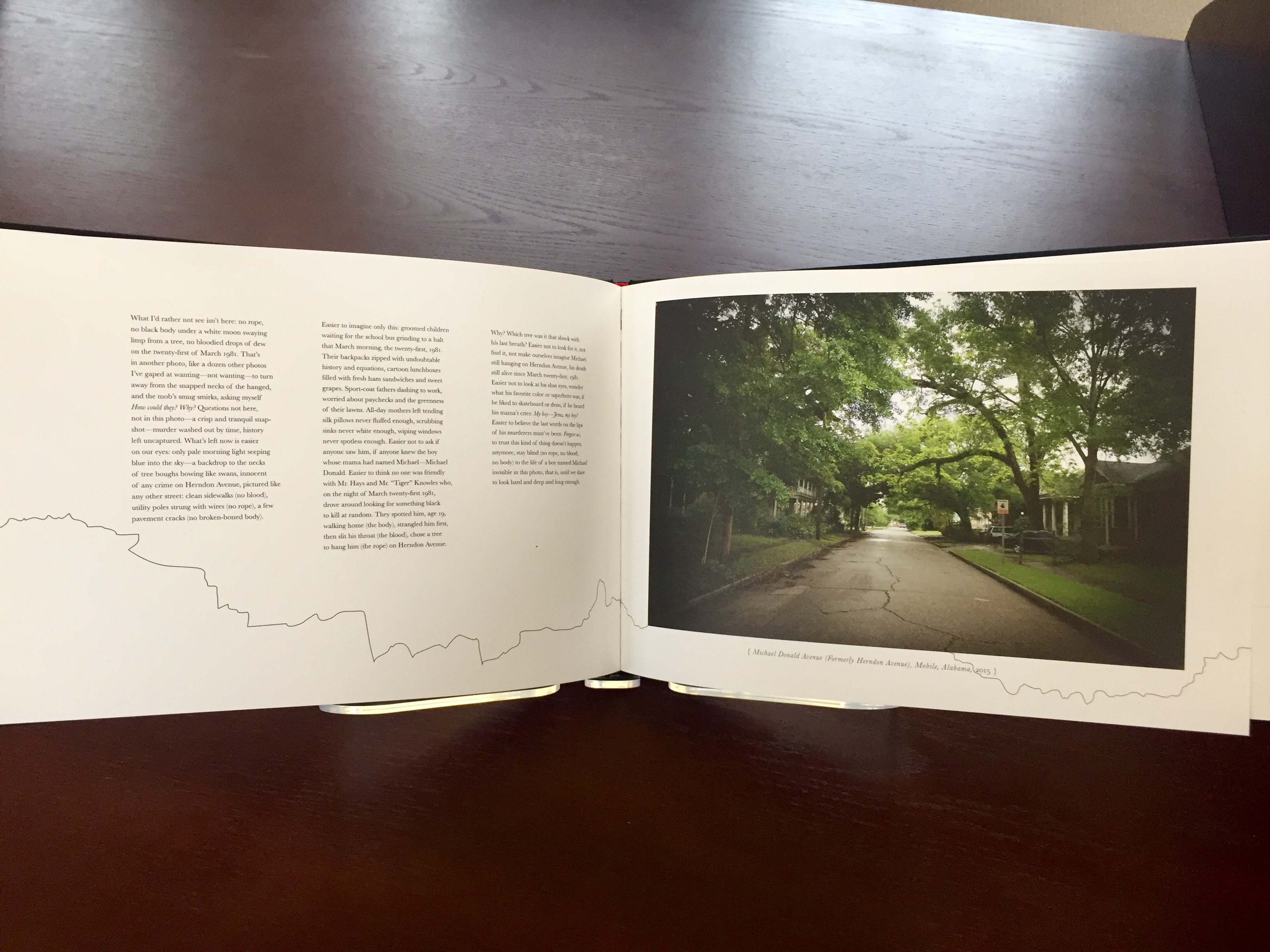

Ultimately, Boundaries aspires not just to depict societal boundaries but to transcend them. In “Easy Lynching on Herndon Avenue,” about the 1981 lynching of Michael Donald, Blanco writes that it might seem “easier” for us “to trust this kind of thing doesn’t happen / anymore,” but he asserts that our divides will persist “until we dare / to look hard and deep and long enough.”

Boundaries thus duly invites us to take a hard, deep, long look at our national history and character, not just to identify what divides us, but in true hope of becoming a more unified people.