Emily Higgs, Special Collections Intern

The first exhibit on display in Special Collections for the Fall 2017 semester is entitled For God and Texas: Southwestern and the Methodist Mission for Higher Education. Inspired by a question I had about why Southwestern and so many other Texas schools are affiliated with the Methodist Church, I curated this exhibit to increase my own familiarity with the history of this institution and to situate Southwestern as a Methodist university.

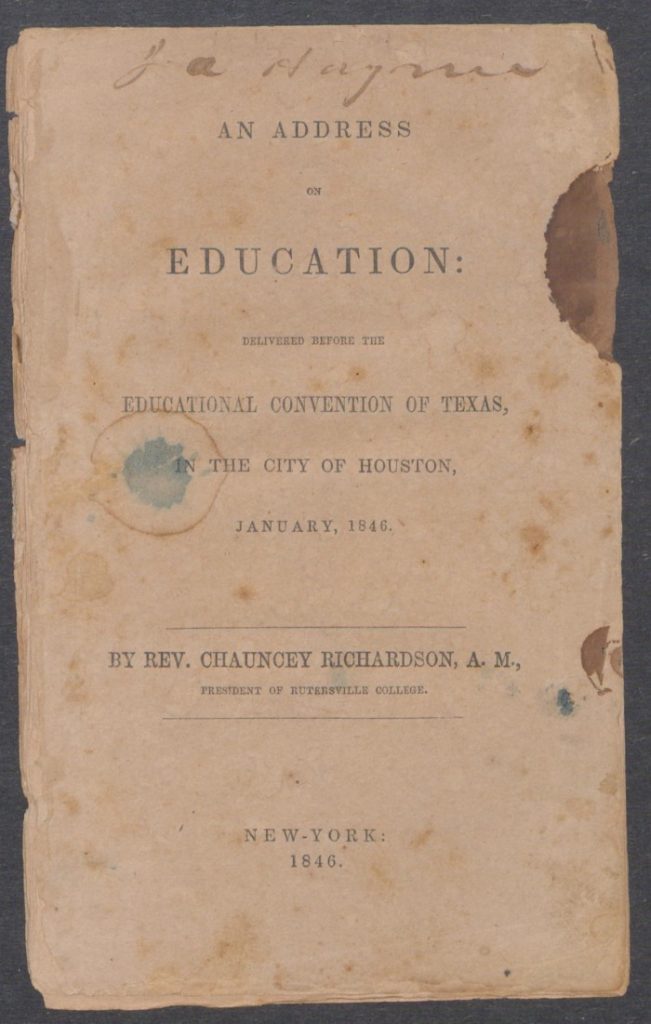

In my preliminary research, the first question I sought to answer was why education was so highly prioritized by the Methodist Church in Texas. This question yielded answers from some unique items in our collection, such as the only known copy of Chauncey Richardson’s published address on education. Chauncey Richardson, a Methodist preacher, was the first president of Rutersville College and presided at what was probably the first educational convention held in the state in Houston in 1846. The convention published Richardson’s Address on Education shortly thereafter. At a time when life in Texas was particularly volatile, Richardson espoused religious education as the key to a stable country. He references the French in his address as examples of powerful minds without the advantage of religious education, “cut loose from all the restraints of conscience and moral obligation” that “deluged France with an ocean of blood.”

Much of the exhibit examines the particular difficulties faced by Methodist schools during the Civil War and its aftermath; several items originate from Soule University, one of the four root colleges of Southwestern. Soule University’s early years were marked by difficulties providing adequate facilities and faculty pay, and the Civil War would bring an abrupt and irreversible decline in its condition. For example, a letter from Soule professor B.T. Kavanaugh to F.A. Mood on Christmas Eve, 1867, gives a tragic account of the state of Soule University in the midst of the yellow fever epidemic; Kavanaugh wrote that the fever has killed Soule faculty and students as well as his own two children. Although Mood took up the presidency of Soule in 1868, the university never recovered from its numerous misfortunes.

Southwestern University founder Francis Asbury Mood recognized these difficulties as a result of too many Methodist schools competing for funding (Methodists opened 21 colleges and universities in Texas by 1900, twice as many as any other denomination) in vulnerable geographical areas. In response to these difficulties, he proposed one central Methodist university for all of Texas, which was later realized as Southwestern University.

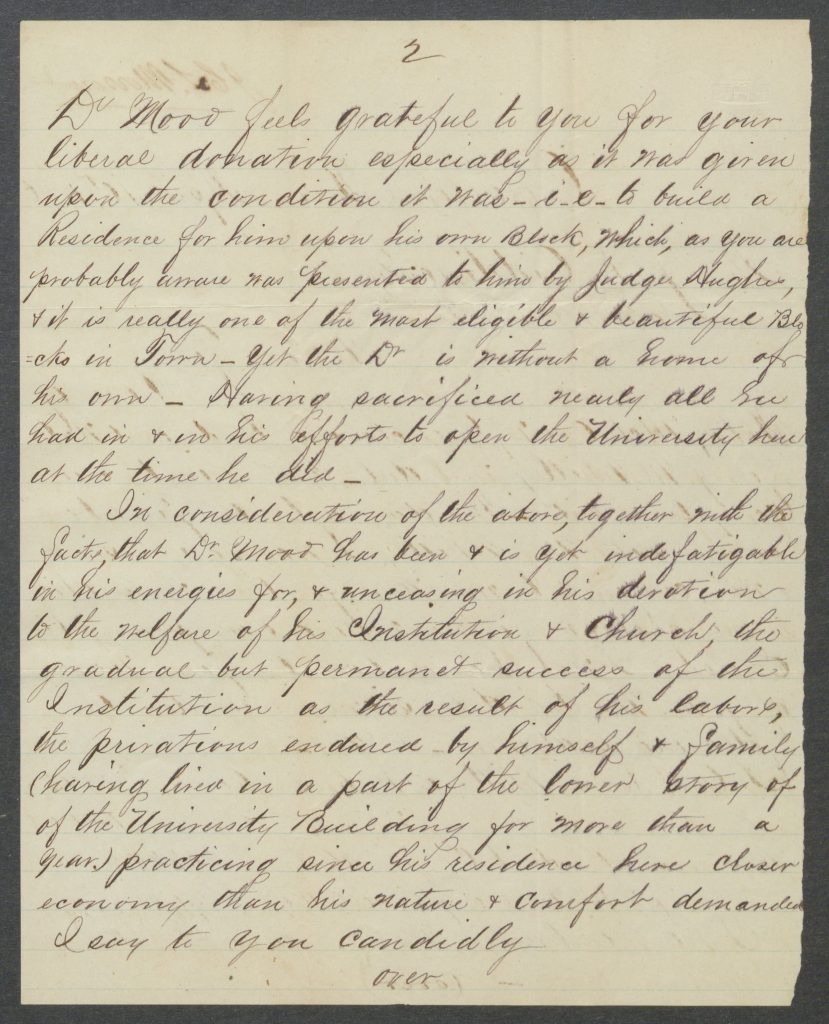

I found in my research that Mood spent the rest of his life fighting to see this vision through; this fight took his finances, his health, and finally, his life. In one of the display cases I have juxtaposed F.A. Mood’s scrapbook, in which he saves clippings from the Christian Advocate extolling the value and rapid progress of the central Texas university movement, with personal letters that reveal a more financially destitute situation for Mood and his university. A letter between Southwestern Trustees J.C.S Morrow and J.D. Giddings in 1876 highlights the sacrifices of Mood and his living conditions in the early years . Morrow writes:

The Dr. is without a home of his own – Having sacrificed nearly all he had in and in his efforts to open the University here at the time he did. In consideration of the afore, together with the facts, that Dr. Mood has been and is yet indefatigable in his energies for, and unceasing in his devotion to the welfare of his Institution and Church, the gradual but permanent success of the Institution as the result of his labors, the privations endured by himself and family (having lived in a part of the lower story of the University Building for more than a year.) practicing since his residence here closer economy than his nature and comfort demanded. I say to you cordially that his is a rare instance of self sacrifice and devotion to his Church and her Institution.

Despite ample evidence that F.A. Mood’s labor and sacrifice were the primary reason that Southwestern survived as an institution, Mood denied this credit in the autobiography he wrote for his children at the end of his life. Instead, in a touching tribute to his wife Susan, he writes:

I here put on record the opinion that the alumni and friends of Southwestern University should erect a monument over your dear Mama as the real founder of the institution. It is she who has borne the burden and heat of the day . . .How little did I anticipate in wedding my little blue-eyed Sue how much of heroism, of patient toil, of wise administration and of pious devotion would in her be thrown around my home.

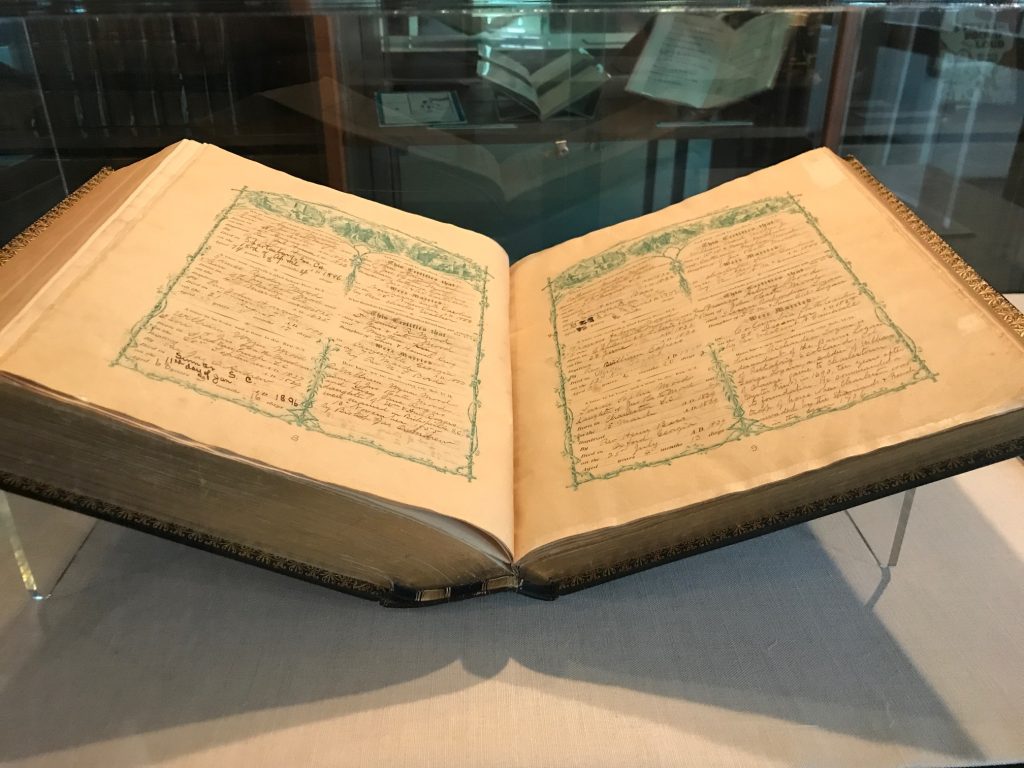

Perhaps my favorite item on display for this exhibit is the Mood family Bible. Printed in 1859 and gifted to F.A. Mood as a member of the Book and Tract Society of the South Carolina Conference, the bible contains a genealogical record of the Mood family. F.A. Mood filled the register by hand beginning with his ancestor Peter Mood, born in Germany in the 18th century, and ending with the births and marriages of his children in the late 19th century. As Southwestern has persisted through the years, so has the Mood family, and the family Bible is a testament to that perpetuity; the family Bible was donated to the Mood Heritage Museum in 1994 by Robert Gibbs Mood III, but the family has continued use of the register after its donation. The most recent entry records the birth of a baby in 2013.

From my experience with this exhibit, I have gained a deeper understanding of the Methodist context of the university, a sense of awe for Southwestern University founder F.A. Mood, and an admiration for the persistence of the university. As incoming and returning students come through the space this semester, I hope they learn something about Southwestern’s history as well as our holdings and mission in Special Collections.